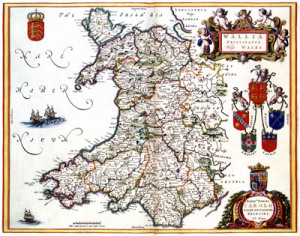

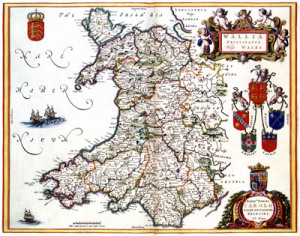

At the moment I’m once again on the hunt for elusive Welsh practitioners in the early modern period. The idea is to try and build up a map of practice, not only in Wales, but across the whole of the country. Once this is done we should have a clearer picture of where practitioners were, but also other key factors such as their networks, length of practice, range and so on.

Working on Welsh sources can at times be utterly frustrating. For some areas and time period in Wales sources are sparse to the point of non-existence. Time and again sources that yield lots of new names in England draw a complete blank in Wales. Ian Mortimer’s work on East Kent, for example, was based on a sample of around 15000 probate accounts. This enabled him to draw important new conclusions about people’s spending on medical practitioners in their final days. For Wales there are less than 20 probate accounts covering the early modern period!

Wales had no medical institutions or universities, so there are no records of practitioners’ education or training. Welsh towns were generally smaller than those in England – the largest, Wrexham, had around 3000 inhabitants by 1700 –and this had a limiting effect on trade corporations and guilds. As far as I can tell there were no medical guilds in Wales between 1500-1750. It is also interesting to note that relatively few Welsh medics went to the trouble of obtaining a medical licence. A long distance from the centres of licensing in London, it could be argued that a licence was simply not necessary. Coupled with this was the fact that there was virtually no policing of unlicensed practice in Wales…only a bare few prosecutions survive.

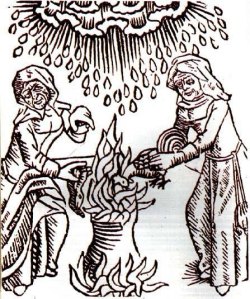

The common perception has long been that there were simply few practitioners in early modern Wales. In this view, the vacuum left by orthodox practice was filled by cunning folk, magical healers and charmers, of which there is a long Welsh tradition. When I wrote Physick and the Family I suggested that there was a hidden half to Welsh medicine, and that if we shift the focus away from charmers etc then a much more nuanced picture emerges. When I began my search in earnest on this project, I was (and still am) confident that Welsh practitioners would soon emerge in numbers.

At the moment, however, the number stands at around the 600 mark. This includes anyone identified as practising medicine in any capacity, and in any type of source, roughly between 1500 and 1750. So, 600 people engaged in medicine over a 250 year period, over the whole of Wales. Admittedly it doesn’t sound much! As a colleague gently suggested recently, this puts the ratio of practitioner to patient in Wales at any given time as roughly 1-50,000!

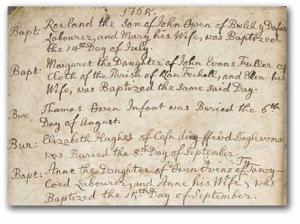

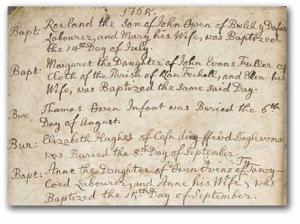

Here, though, the question is how far the deficiencies of the sources are masking what could well have been a vibrant medical culture. How do you locate people whose work was, by its nature, ephemeral? If we start with parish registers, for example, their survival is extremely patchy. For some, indeed many, areas of Wales, there are simply no surviving parish records much before 1700. Add to that the problem of identifying occupations in parish registers and the situation is amplified. How many practitioners must there be hidden in parish registers as just names, with no record of what they did? It is also frustrating, and probably no coincidence, that the areas we most want to learn about are often those with the least records!

Records of actual practice depend upon the recording of the medical encounter, or upon some record of the qualification (good or bad), training, education or social life of the practitioner. Diaries and letters can prove insightful, but so much depends on the quality and availability of these sources. There are many sources of this type in Wales but, compared to other areas of the country with broader gentry networks, they pale in comparison.

All of this sounds rather negative, and it is one of the signal problems in being a historian of medicine in Wales of this period. In a strange way, however, it can also be a liberating experience. I have long found that an open mind works best, followed by a willingness to take any information – however small – and see where it can lead. Once you get past the desperation to build complete biographies of every practitioner you find, it is surprising what can actually be recovered.

In some cases, all I have is a name. Oliver Humphrey, an apothecary of a small town in Radnorshire makes a useful case in point. He is referred to fleetingly in a property transaction of 1689. This is seemingly the only time he ever troubles the historical record. And yet this chance encounter actually does reveal something about his life and, potentially, his social status and networks. The deed identifies him as an apothecary of ‘Pontrobert’ – a small hamlet 7 miles from the market town of Llanfyllin, and 12 from Welshpool. Immediately this is unusual – apothecaries were normally located in towns, and seldom in small, rural hamlets.

The deed involved the transfer of lands from Oliver and two widows from the same hamlet, to a local gentleman, Robert ap Oliver. Was this Robert a relative of Oliver Humphrey? If so, was Oliver from a fairly well-to-do family, and therefore possibly of good status himself? Alternatively, was Robert ap Oliver part of Humphrey’s social network, in which case what does this suggest about the social circles in which apothecaries moved?

Where there is a good run of parish registers, it can be possible to read against the grain and find out something of the changing fortunes of medics. Marriages, baptisms and deaths all point to both the length of time that individuals can be located in a particular place, and how they were identified. In some cases, for example, the nomenclature used to identify them might change; hence an apothecary might elsewhere or later be referred to as a barber-surgeon, a doctor or, often, in a non-medical capacity. This brings me back to the point made earlier about the problems in identifying exactly who medical practitioners were.

An example I came across yesterday was a bond made by a Worcestershire practitioner, Humphrey Walden, “that in consideration of the sum of £3 he will by the help of God cure Sibill, wife of Mathew Madock of Evengob, and Elizabeth Havard, sister to the said John Havard, of the several diseases wherewith they are grieved, by the feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist next ensuing, and that they shall continue whole and perfectly cured until the month of March next, failing which he shall repay the sum of £3”.

Apart from the wonderful early money-back guarantee, this source actually contains a potentially very important piece of information. It confirms that a Worcester practitioner was treating patients in Wales – Evenjobb is in Radnorshire. Walden may have been an associate of John Havard and been selected for that reason. Alternatively, he may have had a reputation along the Welsh marches as a healer for certain conditions, and been sought out for that reason. It strongly suggests the mutability of borders though, and the willingness of both patients and practitioners to travel.

In other cases practitioners pop up in things completely unrelated to their practice. The only record I have of one Dr Watkin Jones of Laleston in Glamorgan occurs because he was effectively a spy for the earl of Leicester, being called upon to watch for the allegedly adulterous activities of Lady Leicester – Elizabeth Sidney. At the very least, however, it confirms his presence in the area, his rough age, and the fact that he was connected to a gentry family.

And so the search continues. My list of potential source targets is growing and I’m confident that a great many more Welsh medics are still there to be found. If, as I suspect, the final number is still relatively small, I still don’t accept that as conclusive evidence of a lack of medical practice in Wales. As the old maxim goes absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. What it might call for is a revaluation of Welsh cultural factors affecting medical practice and, perhaps, a greater and more inclusive exploration of medical practice, in all its forms in Wales.

(This post originally appeared on Alun Withey’s blog dralun.wordpress.com – apologies for cross-posting)