The ‘Landscape of Occupations’ workshop, held at the University of Exeter on the 8th and 9th of April 2014, featured presentations from fifteen scholars, covering an exceptionally wide range of perspectives on the theme of work and occupational identity in late medieval and early modern Europe. Fields examined ranged from agriculture to fine art, and of course included medical practice in many of its early modern forms, in a context which highlighted the parallels, dependencies and contexts which connected them all. Perhaps more importantly the ‘landscape’ of occupations was considered on a range of scales, from macroeconomic surveys spanning centuries and nations, to microeconomic considerations of occupational communities, and nano-studies of family economies.

Combining such diverse perspectives and examples, we were able to reflect upon historians’ approaches to occupational history, and two distinct conceptions of the term ‘occupation’. Many papers approaching the subject from the perspective of economic history emphasized ‘occupation’ as a description of work, while historians working from a social and cultural tradition have focused upon ‘occupation’ as a self-defined, or indeed projected, label of identity. While this might appear to be a paradox, both definitions are naturally equally true, and both reflect the consistent desire, both amongst early moderns and historians, to reduce identity to a simple term, especially when responding to, or describing, change. Attempts at fixing occupational identities to single work activities occurred notably during periods of economic anxiety, including the failed statute regulating ‘one man, one trade’ of 1363, and during the 1560s. Yet, in parallel with contemporary reactionary attempts at regulating social and moral capital through sumptuary legislation, they were both exceptional, and unsuccessful. Thus historians examining either definition face the same challenges in interpreting the complexities and inconsistencies inherent in understanding ‘occupation’.

The presentations all addressed a core set of questions, which while widely shared, pose challenges in reconciling the divergent conclusions that emerge. The questions can be grouped into three broad areas:

- Structural Change. Macro-economic approaches focus upon change over time in large samples, often working with an implicit Smithian notion of specialisation and increasing economic complexity, and relying upon occupational description as an indicator of change.

- Representation and Portrayal. The position of work within the formation of wider entities, as well as the variability of terminology throughout time, location, and as markers of status and power.

- Networks and Lifecycles. Occupation as a fluctuating identity, reflecting changing circumstances of individuals, local communities and especially households.

These approaches each offer compelling conclusions, but the big question that emerged during the workshop is how they might speak to each other. There is a tendency for answers to one of these questions to present challenges to the others. For example, mixed or changing identity is a source of uncertainty in studies of structural change, just as the dynamic of structural change unseats attempts to explore ‘identity’ over time or space. Hopefully, by bringing together scholars working from these contrasting approaches, we can move towards new ways of addressing the question of historical occupations which might address these challenges.

For instance, the core approaches highlighted all emphasize the fact that occupation is less of a matter of individuals, but is rather a subject permeated by external factors including markets and employment structures, social and religious affiliations, changes in circumstances, abilities, and strength, and, perhaps especially, the influence of institutions. Papers examining the medieval period cast these external influences in a particularly clear light, including bakers’ delicate balancing of completing influences of market and assize, while the occupational origins of late medieval archers revealed the vexed questions of formal and implicit feudal obligation, age and strength. Less overt, but equally important, were questions of social credit, reputation, and brand, as seen in discussions of craftspeople operating in the fields of scientific instruments and fine art, as well as those facing failure in business and seeking to escape their debts.

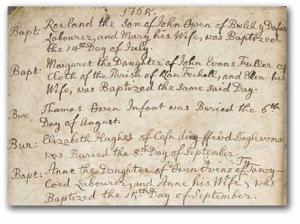

The ‘landscape’ of occupations was highlighted in the sense that work and occupation can best be understood within the contextual environment of the other occupations and identities with which it co-existed. Moreover, occupational identities were negotiated, in all respects, in unique circumstances, and just as different terms could be used to describe the same ‘work’ in different contexts, so too could the same label carry different meanings in, for example, urban and rural settings. Papers focusing upon local case studies, such Newcastle keelmen, and Bristol medical practitioners highlighted the importance of contextual understanding and local variation to draw together these multiple and shifting influences, even when following broadly quantitative approaches.

Again addressing questions of both ‘work’ and ‘identity’ is the question of the skill content of occupations. On one level skill can be classified and ascribed to occupational identity, and was in many cases judged as such by contemporaries, as seen in the context of Portugal’s remarkably centralised yet contentious system of medical licensing. Yet, as Margaret Pelling emphasized in the keynote lecture, the varied nature of skills transmitted through apprenticeships included the ‘soft’ skills of social interaction and successful business judgement. How effective, and how definitive, was apprenticeship as the dominant western European means of occupational education?

While there seems little prospect of a single economic theory of occupation, as some might wish for, the workshop served as a wonderful opportunity to re-examine familiar people, trends, and events, in new lights. From the perspective of the ‘Medical World of Early Modern England, Wales and Ireland’ project, we have resolved both to increase the depth of local case studies to investigate qualitative differences within ostensibly equivalent occupational identities, and to exploit data that we have already collected to refocus upon medical practitioners as part of household and familial economies, as well as occupational inheritances and the lifecycle of medical training and occupation.

Full list of speakers and papers:

Human capital formation from occupations: The ‘deskilling hypothesis’ revisited

Alexandra M. de Pleijt, (Utrecht University) and Jacob L. Weisdorf, (University of Southern Denmark, Utrecht University and CEPR)

Civilians at war: English archers and their occupations 1350-1415

Sam Gibbs (University of Reading)

Debt and Occupation: The Trades of Debtors Imprisoned and Absconded in the 1720s

John Levin (University of Southampton)

‘Working lives and the historical record in Newcastle upon Tyne, 1600-1710’

Andy Burn (Durham University)

Movement and interconnectivity in the ‘scientific’ instrument trade of early modern London

Dr Alexi Baker (University of Cambridge)

Bakers and Occupational Specialisation, 1350-1550

James Davis (Queen’s University Belfast)

Managing uncertainty and privatizing apprenticeship: status and relationships in English medicine

Margaret Pelling (University of Oxford)

Medical career trajectories in Early Modern Portugal

Laurinda Abreu (University of Évora)

Medical Practice in Bristol, c. 1500 – c. 1800

Jonathan Barry (University of Exeter)

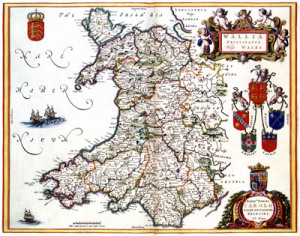

Plotting Practitioners: GIS and Spatial Patterns in Early Modern Medical Provision in England and Wales

Justin Colson (University of Exeter) and Patrick Wallis (London School of Economics)

Working from the local to the national. Reconstructing labour relations in the Northern Netherlands, c. 1600-1800

Daniëlle Teeuwen (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam)

Early modern rural by-employments: a re-examination of the probate inventory evidence

Sebastian A. J. Keibek (presenting) and Leigh Shaw-Taylor (University of Cambridge)

‘The Honest Tradesman’s Honour’: Work and Identity in Seventeenth-Century England

Mark Hailwood (St Hilda’s, Oxford)

Occupational and religious identities: the example of the Johnson Company 1542-c.1557

Laura Branch (NUI Gallway)

Mary Beale, Artist 1633-1699

Sarah Birt (Birkbeck College)